The building is a narrow-windowed, red-brick, monolithic structure on the corner of Plum St. and W. Court St. in downtown Cincinnati. It looks like an abandoned public library from the 1970s. Its appearance is especially stark when contrasted with the distinct, stately Cincinnati City Hall, Isaac M. Wise Temple, and Cathedral Basilica of St. Peter in Chains which are all nearby. However, appearances can be deceiving. This building, the Lloyd Library, is one of the most interesting and largest repositories of pharmaceutical information and old botanical texts in the country with over two hundred thousand books. It is a rare gem and something the city should be proud to showcase. Many say the Lloyd Library is better known outside of Cincinnati, which I can imagine. Its primary use is by those interested in the medicinal properties of plants. Its history harkens back to a fascinating time in which the practice of medicine in the United States was standardizing, professionalizing, and advancing in its understanding of disease and disease treatment. Its history is exemplified both by the library's founder, John Uri Lloyd, and the institution he was most closely associated with, the Eclectic Medical College of Cincinnati (EMI). The library also revealed a couple of interesting stories that were very personal to me, as will be discussed at the end of this post. It is important to note that most of the general history below came from the books John Uri Lloyd: The Great American Eclectic by Michael A. Flannery and A Profile in Alternative Medicine: The Eclectic Medical College of Cincinnati: 1835 – 1942 by John S. Haller.

Medical Education was a Free-for-All in the United States in the 19th Century

Medical education was largely a free-for-all in the United States in the 19th century. There was a great deal of variability in the quality of the medical schools themselves as well as post-education apprenticeships in hospitals. Few medical schools were affiliated with a college or university hospital. There was an overreliance on classroom learning rather than clinical exposure. Medical schools were almost entirely profit-driven, with a board of directors paying dividends to investors. As a result, medical schools were less likely to be mission-driven endeavors with a broader social goal. Furthermore, medical licensing post-apprenticeship was lax and enforced variably by states. This is the historical context in which the EMI was founded. It was also when John Uri Lloyd would begin his teaching and research.

Competing Sects of Medicine Arose in Chaos

The medical profession was regarded poorly in the 19th century. The dominant sect then and now, allopathic medicine, derived its legitimacy from its lineage to the historically dominant European models of medicine. Allopathic medical schools graduate physicians with "M.D." after their name. Then and now allopathic physicians dominate staffing at most hospitals, state medical societies, and state board examiners. Despite this, allopathic physicians practiced medicine in a way that was widely considered barbaric. Their "cures" included bloodletting, cupping, and blistering. These brutal treatments extended back to antiquity.

Alternative sects arose in response to the dominance of allopathic medicine. Models such as homeopathic medicine and Thomsonism emphasized different methods of diagnosing and treating disease. For example, homeopathic medicine emphasized plant-based therapies and the concept of "like cures like," which is a belief that treatments that induced a symptom such as fever in a healthy individual could treat a fever in an unhealthy individual. Thomsonism encouraged patients to manage their own medical care using home remedies. The eclectics also emphasized plant-based treatments that were gentler on patients and intended to target specific symptoms of disease, though not in the manner of "like cures like." The problem with all these alternative models of medicine is that none focused on diagnosing and treating diseases themselves. Remember, this era of medicine preceded the germ theory of disease.

The Eclectic Medical College of Cincinnati (EMI) Is Founded in the 1820s and Grows Rapidly

It was in the above context that the EMI and later the Lloyd Library were founded in Cincinnati, Ohio. No longer present, the EMI building was caddy corner to the current location of the Lloyd Library. The EMI originated in New York City, though the school migrated to Columbus and then Cincinnati. It was a disreputable institution in its early years because it was focused on promoting the prescription of "green drugs" developed by a professor that were ineffective. It took Dr. John Milton Scudder, who led the EMI from 1861 – 1894, to improve the EMI's reputation. Dr. Scudder dropped "green drugs." He replaced them with "Specific Medications" developed and produced through a relationship with the pharmaceutical manufacturer H.M. Merrell and Company in Cincinnati. Specific Medications were produced with more consistency in purity and concentration. They were also more effective, though likely not in the same way, for example, ibuprofen improves pain, or an antibiotic eliminates bacteria. The EMI had the largest medical school enrollment in the United States during Dr. Scudder's time as head. It was also during this time, in 1878, that Dr. Scudder hired the pharmacist John Uri Lloyd, the Lloyd Library's namesake, to be the professor of chemistry and pharmacology.

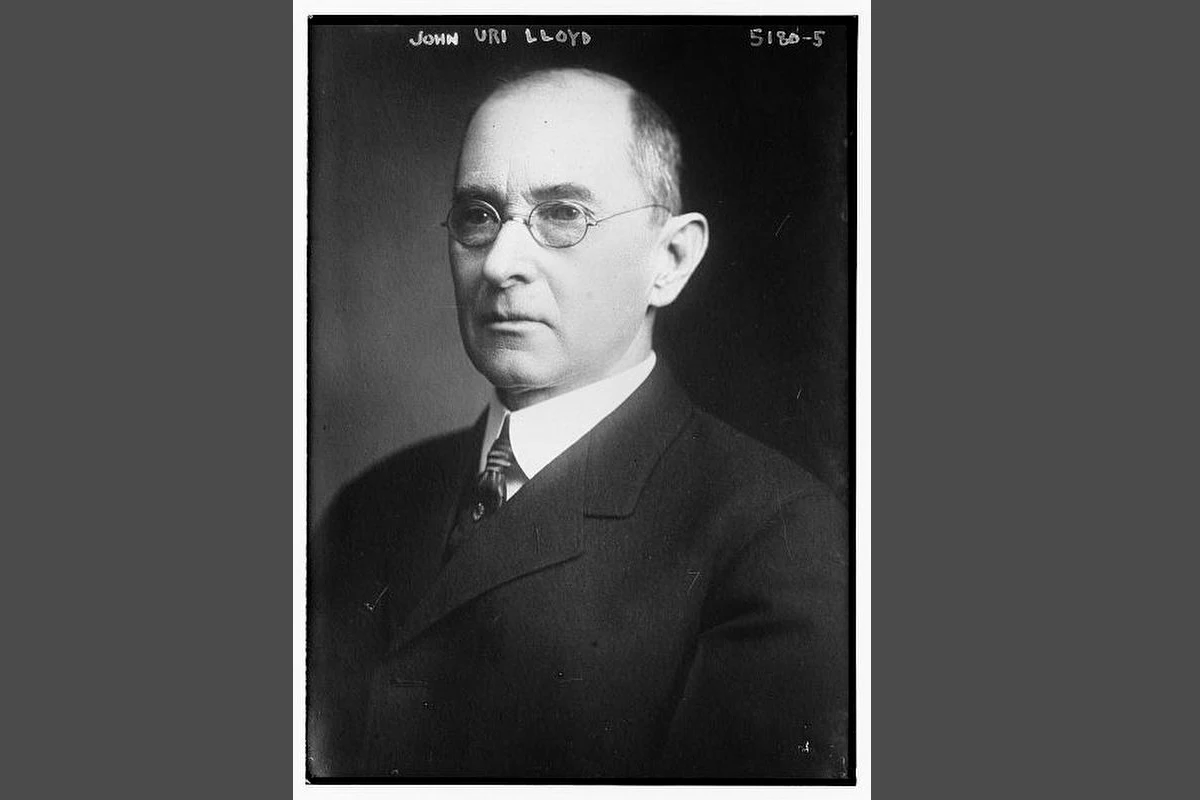

John Uri Lloyd was an Academic, Research Pioneer, Businessman, and Popular Author

John Lloyd, a native of Northern Kentucky through-and-through, was the most reputable and financially successful professor the EMI ever had. While he was intimately linked to the EMI locally his professional and academic reputation was international and independent of the reputation of the school. To understand John Lloyd is to understand his library. He became one of the most respected professors by students soon after he started teaching. It was with John Lloyd's assistance and that H.M. Merrell and Company would produce Dr. Scudders "Specific Medications."

H.M. Merrell and Company would become Lloyd Brothers Pharmacists, Inc. in 1885, owned and managed solely by John and his brothers. This would be the primary source of family wealth. It is remarkable how well each of the Lloyd brothers fit into their roles. John Lloyd was the head of the company as well as the head of research and development. His older brother, Nelson, was the business manager. His younger brother, Curtis, was probably the most interesting. The consummate playboy, he was tasked with traveling the world collecting specimens as well as rare books and texts for what would eventually become the Lloyd Library. I would later learn that these texts included books on the occult, alchemy, and other pseudoscientific endeavors. A shelf in the library displays a hilarious series of two photos of Curtis in what may be, according to the librarian on our tour, one of the first memes ever created, albeit unintentionally. Curtis Loyd died unmarried and without kids. His estate still funds the maintenance of the Lloyd Library to this day as well as research grants to artists and scientists.

John Lloyd not only produced the medications eclectic physicians were prescribing, but he also co-authored American Dispensary, which was the eclectic answer to the US Pharmacopeia (USP), the primary, allopathic repository of pharmacological information in the United States. John Lloyd's other contributions to pharmacological academic literature were significant as well. Interestingly, elixirs were a craze during this time. Elixirs were mass-produced and marketed mixtures of diluted substances purported to have medical benefits, but which were fraudulent. Little-to-nothing was known of their composition, purity, and concentration. John Lloyd wrote Elixirs: Their History, Formulae, and Methods of Preparation in response to this craze to establish some empirical rigor to the production of these mixtures, which was harming his business and patients.

He won the highest award in pharmacology research, the Remington Honor Medical, three times. He advanced research in colloidal chemistry and capillarity in drug development almost 50 years prior to the validation and application of these methods in the production of pharmaceuticals. He discovered a buffered alkaloid called fuller's earth that allowed medications to be functionally preserved and absorbed in the gut, thereby allowing oral administration of some medications. And, late in his career, the significance of his expertise came full circle when he was invited to contribute to the USP itself.

His company produced numerous medical patents, the most important of which was a cold sill extractor that allowed for the extraction of compounds from plants without using heat. This was thought to better preserve the structure of plant medicinal compounds. The cold sill extractor was in use in industrial pharmaceutical manufacturing until the 1960s. There is an original cold sill extractor in the library. It is much smaller than I would have expected it to be.

John Lloyd was not only a businessman and academician, but also a famous writer. In fact, he used money earned from his fiction writing to fund the purchase of texts for the Lloyd Library. His only novel that remains in print is called Etidorpha. It is a fantasy novel about a man's run-in with a mysterious being and their journey to the center of the earth. I have heard it is not a particularly good book. However, it remains popular with occultists due to its broader themes of hidden worlds filled with secret knowledge. The original illustrator for Etidorpha was the Cincinnatian J. Augustus Knapp. It is worth looking up these drawings as well as others he drew for occultists. They are haunting and mysterious. Some suspect this book, which is filled with anthropomorphic fungi and other strange visuals, indicates that John Lloyd experimented with hallucinogenic plants. Many well-known authors were fans of the Etidorpha, including the famous horror writer H.P. Lovecraft.

John Lloyd also wrote a series of popular novels referred to as the Stringtown Series. The Stringtown Series was of the "color stories" genre popular in the United States at the time. They can best be thought of as that era's Young Adult (YA) novels. Color stories were typically set around the Civil War and emphasized regional dialects and made distinct cultural references that were fast disappearing in an industrialized nation.

His success led to his recruitment into government and politics. He was a fishing buddy of President Grover Cleveland. He was a vocal proponent of the National Pure Food and Drugs Act, which was passed in 1906 and was the precursor to the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). He was sent by the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) and the Smithsonian Institue to investigate plant-based medications. He was a member of the grand jury that helped clean up politics after the fall of the famous boss George Cox political machine in Cincinnati. And he was even asked to be the Democratic candidate for mayor of Cincinnati, which he refused.

Unlike John Lloyd, the EMI Failed to Evolve With the Times

John Lloyd's career thrived despite the gradual decline of the EMI. The EMI, and eclectic medicine generally, disappeared for many reasons, not the least of which was its failure to keep up with the reforms to medical education sweeping North America in the early 20th century. These reforms were pioneered by a man named Abraham Flexnor. Born in Louisville, Kentucky, Abraham owned a medical school but was not a physician himself. He was commissioned by the Carnegie Foundation at the request of the American Medical Association's Council on Medical Education (CME) to review the state of medical education in the United States and Canada. This was significant because the CME was, and remains, a powerful force in the education of medical students, residents, and physicians to this day. It is also significant because the dominant allopathic medical sect dominated the CME, thereby virtually guaranteeing the demise of the eclectics. The CME was the first to recommend the now-standard 4-year medical school curriculum consisting of 2 years of pre-clinical scientific study followed by 2 years of clinical rotations. The Carnegie Foundation released the Flexnor Report in 1910. The report advocated for more rigorous admissions and graduation standards. For example, most medical schools did not even require an undergraduate education prior to matriculation. It advocated for centralizing medical schools in universities with the model being Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland. It advocated for state medical boards to be more selective in who they licensed. Finally, it demanded that medical school professors be hired full time and engaged in scientific research like the German medical training model.

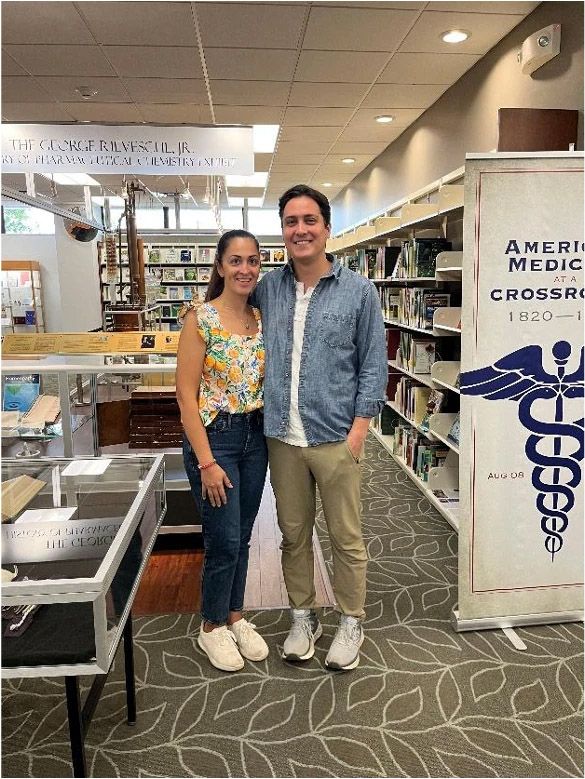

My wife and I recently attended the Lloyd Library's exhibit American Medicine at a Crossroads 1820 – 1910. A glass case held two documents. The first was a map of the United States with all the medical schools marked. The second was a map of the United States with the anticipated number of medical schools after implementation of the Flexner report. The density of dots on the second map was less than half the first. It was astounding. The Flexner Report's implementation through the CME effectively led to the closure of the sectarian medical schools, including the EMI, while preserving the dominant allopathic medical schools, albeit reformed in their traditional methods of treating disease

Fara and me at the Lloyd Library for the American Medicine at a Crossroads 1820 – 1910 exhibit

It was clear in hindsight that the EMI, and sectarian medicine in general, would not survive the reforms recommended in the Flexnor Report. The EMI did not pursue an affiliation with a university hospital. It did not invest in research facilities for professors and students. It was late in making pre-medical education requirements more rigorous, waiting until 1911 to require a college degree prior to admission. And, despite multiple attempts, the alumni were not forthcoming with donations, presumably because of the stigma associated with being from the eclectic medicine sect. Most alumni wanted to hide this fact and blend in with the broader allopathic medical system. In the end, the EMI would never receive the necessary designation from the CME that would have allowed the institution to receive public funding or even allow their students to gain admission to formal residency training. In fact, the CME considered the EMI functionally "extinct" starting in 1920, 22 years before the closure of the institution. The EMI's last graduating class was 1939. The school closed for good in 1942, when the library and school records were transferred to the Lloyd Library, where they still exist today.

The improvements made to medical education by the CME were vast and important. However, I wonder whether something was lost with this process. I wonder whether some wisdom from the eclectic sect of medicine has relevance today. For example, John Lloyd himself argued that the new, more stringent education requirements would likely discourage individuals from pursuing a career as a local family physician in a small town. This is absolutely something we are having difficulty with today. Many are asking whether four years of medical school is necessary, specifically the two pre-clinical years. Furthermore, we may be missing some potential breakthrough medications by not establishing a more robust investigation of potentially therapeutic plant compounds. A short search online of research institutions focused on the medicinal properties of plants identified only The Appalachian Natural Products Research Program at Marshall University in West Virginia as well as programs at the University of Kansas, The Ohio State University, and Emory University. One of the earliest effective chemotherapeutic medications, paclitaxel, was isolated from the Pacific yew tree during government-funded research on therapeutic plant compounds in the 1960s. The Lloyd Library has an instrument on display that was first used to isolate this compound. What potential breakthrough medications could be in our backyard?

The Lloyd Library Revealed Two Personally Significant Stories

The Lloyd Library contains two personally important pieces of history.

First, I discovered that the medication diphenhydramine (Benadryl®) was developed in Cincinnati. This was one of the medications that saved my son's life when he experienced an anaphylactic reaction.

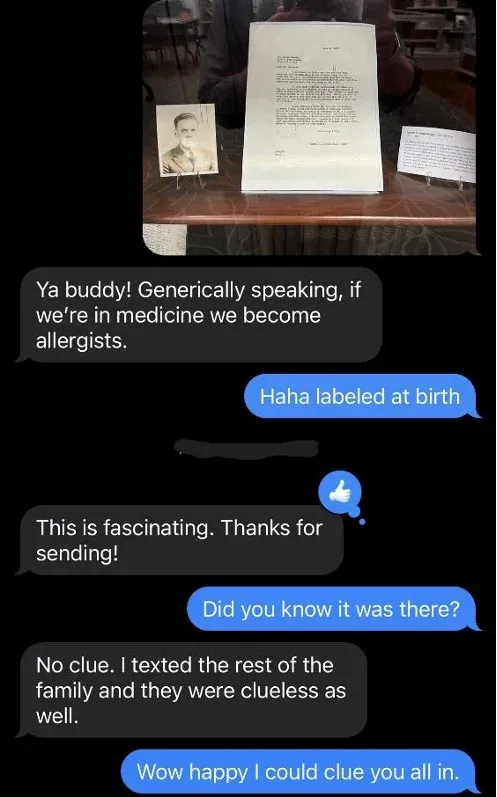

I found the second piece of history in a display that felt a bit out-of-place next to the many photos of John Lloyd and his brothers. The glass display included a photo of a man, his admission letter to medical school, and a small note. His last name was Khory, which, according to my Arab friends, is likely of Lebanese origin. I assumed his background made the letter significant as non-whites were unlikely to be admitted to medical school in the 1930s. A note next to the admissions letter explained that this physician founded an allergy practice in Cincinnati (Cincinnati Allergy & Asthma Center), that his daughters took it over, and that their sons subsequently took it over. I soon realized that the physician displayed was the grandfather of a person who is not only my son's allergist but also my high school classmate. I reached out to him, sending him a photo of the display. Not only had he never seen this but none of his family knew this display existed.

The text exchange between my colleague and I regarding his grandfather's medical school admissions letter

The Lloyd Library Evoked a Sense of Wonder in Me

The Lloyd Library is a fascinating place. Most museums are, in my opinion. But I wondered why it felt so special despite its undistinguished appearance. I think the answer is because of the sense of wonder the library engendered. The Lloyd Library is filled with an incomprehensible number of exotic plant specimens and old books that reference a now-extinct sect of medicine in addition to other esoteric subjects. I felt like I had come upon an intentionally hidden repository of information. I have experienced this feeling twice before.

The first experience occurred fifteen years ago when I was traveling in Paris shortly after college. I had just completed a year teaching at Weil Cornell Medical College in Doha, Qatar. I was ready and open for an adventurous summer before returning to the United States and medical school. I was invited by a friend from Cornell to visit their favorite museum in the city, a pathological specimen collection housed in a medical school. I cannot remember the medical school and, when doing a cursory search, found that at least two of them have shut down since I visited in 2010. The collection of glass jars filled with diseased organs and body parts – including heads – was housed in an old room within the campus. There was no front desk, only an employee available to take money to peruse the collection. It was of obvious interest to me as a soon-to-be medical student. But, as importantly, I felt like I was one of the few people in the world to have discovered this discreet institution. The displays reflected their age. While well-maintained they displayed labels from the 19th and early 20th centuries. The specimens contained there must have felt like a repository of esoteric knowledge to those who witnessed it when it first opened. Remember, this museum opened at the same time as the EMI was educating students and John Lloyd was making advances in the field of pharmacology. Those who created this space knew much less than we do now about the diseases these patients suffered from. I felt like I was in the Restricted Section of the Hogwarts Library.

A statue at the pathology museum I visited in Paris, France. Notice all the crates stacked around it. This pathology museum was not well-attended.

I have sought out similar institutions in the cities I have visited. One such institution is in Los Angeles, California, a city we visit frequently for family. The Museum of Jurassic Technology is part art-installation, part museum, and part cabinet of curiosities. The traditional German name given to a cabinet of curiosities is wunderkammen, or house of wonder. These institutions were rooms filled with collections of strange and exotic specimens collected by wealthy patrons who had originally housed them in a private collection. While some of these specimens were real, many were not. In fact, it was often difficult to tell which were real and which were not. They were popular pre-Renaissance and prior to Enlightenment era concepts of empiricism and truth seeking using the human senses that resulted in the transition from these wunderkammen to the modern, public museums we have today that started in the 19th century.

The front entrance to The Museum of Jurassic Technology in Los Angeles, CA

The building itself is a non-descript storefront on a busy street in Culver City. The website appears to be a relic of the late nineties and early 2000s, with grainy, incongruous text and little in the way of actual information about the place. The interior is relatively small and filled with winding paths bathed in dim, warm light. Old microphones with a quiet voice on the other end describe the displays, each of with is filled with old documents, machines that may or may not be real, and long, complex histories of people and places that feel legitimate but also like they may be more appropriate for a Ripley's Believe it or Not! I read the Pulitzer finalist book on the museum called Mr. Wilson's Cabinet of Wonder by Lawrence Weschler. He did research on some of the permanent and earlier temporary exhibits, finding much truth – though not complete – even in the stranger family histories described. My two favorite "exhibits" included a detailed history of a little known Russian scientist who developed plans for interplanetary travel in the late 19th and early 20th centuries (likely untrue) and a beautiful exhibit on Islamic architecture, the architectural details of which I know are true.

The Lloyd Library is an academic institution that does not intend to make any artistic or philosophical statements like the Museum of Jurassic Technology. Furthermore, it is still in use by researchers, unlike the pathology museum I visited in Paris. But, like the pathology museum and the Museum of Jurassic Technology, the Lloyd Library in Cincinnati, Ohio encourages a sense of curiosity and wonder in a way that few museums currently do. I would encourage everyone in the area to visit.

References

- Flannery, Michael A. John Uri Lloyd: The Great American Eclectic. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1998.

- Haller, John S., Jr. A Profile in Alternative Medicine: The Eclectic Medical College of Cincinnati, 1845–1942. Kent State University Press, 1999.

- Smith, RJ. "John Uri Lloyd: To Infinity and Beyond." Cincinnati Magazine, April 2015. https://www.cincinnatimagazine.com/citywiseblog/john-uri-lloyd/

- Weschler, Lawrence. Mr. Wilson's Cabinet of Wonder. New York: Pantheon Books, 1995.

Disclaimer

This blog post is for educational purposes only and does not constitute direct medical advice. It is essential that you have a consultation with a qualified medical provider prior to considering any treatment. This will allow you the opportunity to discuss any potential benefits, risks, and alternatives to the treatment.

Book Your Consultation

Take the first step toward enhancing your natural beauty by scheduling a personalized consultation with Dr. Jeffrey Harmon. As a double board-certified facial plastic surgeon trained by the pioneer of the extended deep plane facelift, Dr. Harmon offers expert guidance and care. Whether you're considering surgical or non-surgical options, our team is here to support your journey to renewed confidence.