This information is adapted from a presentation given to physician groups and a series of videos available online. It is important to seek not only a fellowship-trained but also a double board-certified facial plastic surgeon if you have aesthetic concerns about your face and/or neck.

Source: Martin, Paula J. Suzanne Noel: Cosmetic Surgery, Feminism and Beauty in Early Twentieth-Century France. Burlington, Vermont: Ashgate, 2014. Print.

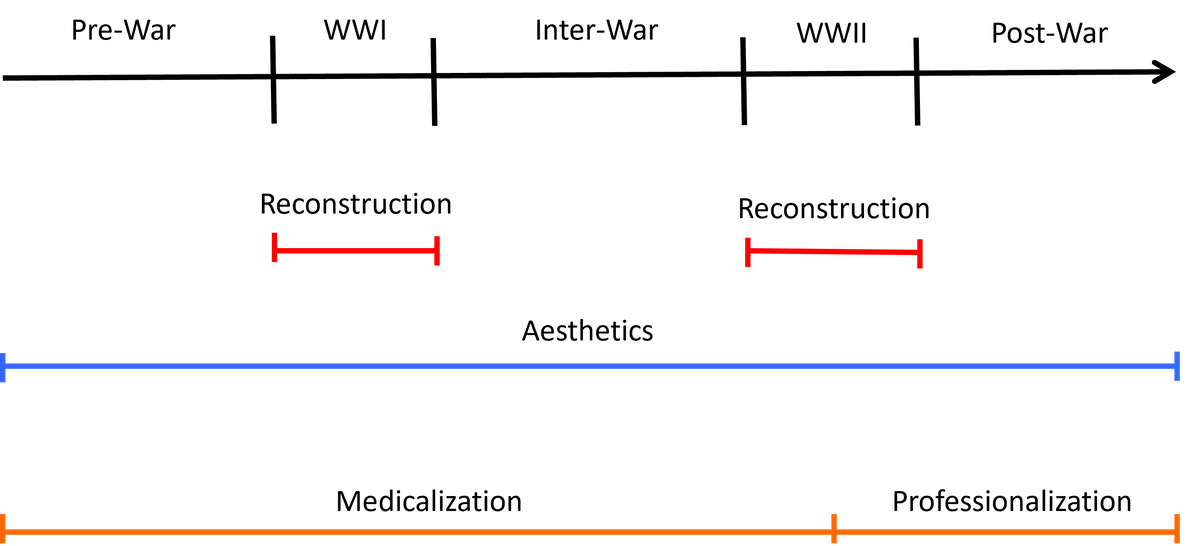

Timeline

The history of facial plastic surgery is a story of heroes and charlatans who navigated a nascent subspecialty developing shortly after the invention of anesthetic agents. While its true origins are ancient, its modern origins begin in the late 19th and early 20th century, immediately before World War I. The best way to understand the modern history of facial plastic surgery is to visualize a timeline extending from a “pre-war” period through World War I, an “inter-war” period, World War II, and the immediate “post-war” period. This timeline is the skeleton on which the history can be fleshed out. Advancements in cosmetic facial plastic surgery developed gradually over this period. World War I and World War II were punctuation marks during which the reconstructive side of facial plastic surgery made great, rapid advancements because the war wounded were surviving increasingly severe facial trauma. The field of facial plastic surgery became medicalized – crystalized into its own coherent field of medicine with its own philosophies and techniques – from the pre-war period to World War II. Facial plastic surgery professionalized – formed a governing body, formal inclusion and exclusion criteria, and a formal delineation of the boundaries of the practice of the field – during World War II and the post-war period. The history below was gathered from reading the referenced books and combining this information into a story of a field of medicine I am proud to be a member of. The individuals discussed here are only a small fraction of those practicing facial plastic surgery at the time. Their stories simply exemplify the evolution of the field in a coherent way.

Early History - Reconstructive Surgery

The earliest facial plastic surgery procedures were developed to repair the nose. The Italian physician Gaspare Tagliacozzi wrote the first textbook on plastic surgery in the Western world in 1597. Called The Surgery of Defects by Implantations, the book includes instructions on a procedure used to reconstruct the nose of patients who contracted syphilis, which destroys the supporting cartilage of the nose. It was a tortuous procedure requiring multiple operations over the course of 3 to 5 months. The procedure utilized skin from the inner arm and forced patients into an uncomfortable, contorted position during the entire reconstructive period.

The caste of potters on the Indian subcontinent developed a much more elegant technique hundreds of years prior to reconstruct the noses of individuals who had theirs removed as punishment for crimes utilizing tissue from the forehead. This technique remained unknown in the West until the early 20th century. Joseph Constantine Carpue, a British army officer, introduced the technique to the West in 1914 and published An Account of Two Successful Operations for Restoring a Lost Nose from the Integuments of the Forehead in 1916.

World War I and II would accelerate advancements on the above techniques by necessity.

Source: Meikle, Murrary C. Reconstructing Faces: The Art and Wartime Surgery of Gillies, Pickerill, McIndoe & Mowlem. Otago University Press, 2013. Print.

World War I - Reconstructive Surgery

There was a rapid innovation in the field of reconstructive facial plastic surgery during World War I when approximately 15% of the soldiers who survived trench warfare experienced facial injuries. Ernest Hemmingway wrote eloquently about these survivors:

There were other people too who lived in the quarter and came to the Lilas, and some wore Croix de Guerre ribbons in their lapels and others also had the yellow and green of the Medaille Militaire, and I watched how well they were overcoming the handicap of the loss of limbs and saw the quality of their artificial eyes and the degree of skill with which their faces had been reconstructed. There was always an almost iridescent shiny cast about the considerably reconstructed face, rather like that of a well packed ski run, and we respected these clients more than we did the savants or the professors.

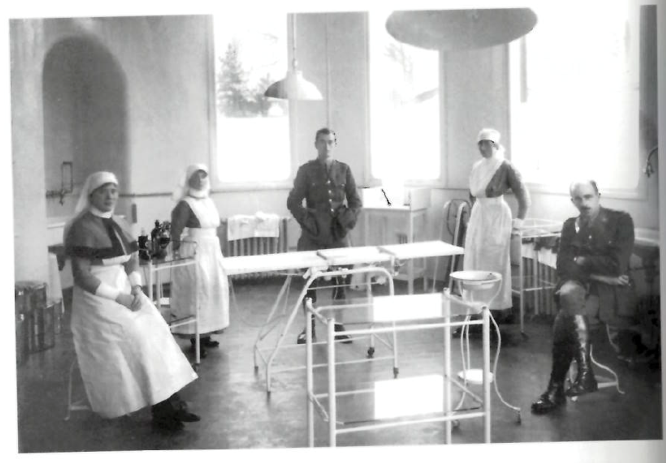

World War I made heroes out of many surgeons, including the New Zealand-born Ear, Nose and Throat (ENT) surgeon Harold Gillies. Initially stationed in France, he returned to England, where he attended medical school, to Cambridge Hospital in Aldershot then to Queen’s Hospital in Sidcup, Kent when Aldershot was of insufficient size to care for the number of wounded. The hospital at Sidcup was founded specifically for those with facial injuries. In fact, it is considered the birthplace of modern reconstructive plastic surgery. Approximately 8000 maxillofacial procedures were performed during its busiest period from 1917 to 1921. The wards housing the most gruesomely injured soldiers were called the “chamber of horrors” by other patients. Mirrors were banned at the hospital during this time.

Harold Gillies wrote Plastic Surgery of the Face in 1920 based on this wartime experience. His book describes multiple innovations including the tubed pedicle, which allowed him to transfer skin from one area of the face to another. However, he also made poor recommendations in his textbook. For example, Harold Gillies insisted on the value of the use of bovine (cow) cartilage for nasal reconstruction despite the discovery of transplant immunity.

Source: Meikle, Murrary C. Reconstructing Faces: The Art and Wartime Surgery of Gillies, Pickerill, McIndoe & Mowlem. Otago University Press, 2013. Print.

World War II - Reconstructive Surgery

The need for plastic surgeons during World War II surged beyond the needs of even World War I. Unfortunately, the total number of plastic surgeons in the United Kingdom during World War II was only 4, including Harold Gillies. As a result, a plastic surgery hospital was built for each of them.

Dr. Gillies settled in Rooksdown House during World War II where he founded The Plastic and Jaw Unit in 1941. They become very busy after the battle and evacuation at Dunkirk. Dr. Gillies was training a few new surgeons at a time during this period, mostly Americans and mostly informally. This is because there were no formal plastic surgery residencies at the time. Harold Gillies would not found the British Association for Plastic Surgeons until 1946. His influence on future generations would be immense, however, as exemplified by the Brazilian plastic surgeon Ivo Pitanguy, whose life will be discussed later.

Harold Gillies was a practical joker. He would disguise himself to potential applicant physicians and chat with them in the hall prior to their scheduled interview as described by one of those applicants:

At the outbreak of the Second World War a plastic and jaw unit was established by Sir Harold Gillies at Rooksdown House, Basingstoke. In 1954 I applied for a post in plastic surgery. The subsequent interview was held at the hospital, a strange looking building which had been the private block of Park Prewett Hospital. On inquiry at the porter’s office, I was directed by an elderly gentleman to wait in the main hall along with the other candidates. Being last in line for interview I was left in glorious isolation until joined by the porter who proceeded to make conversation. His opening gambit was to inquire how much fishing I had done in Ireland, to which I replied in the negative. As to other sporting activities, I admitted that there were none at that particular time. There followed a few desultory questions about my surgical activities, which I thought were none of his business. Returning to the question of sport, he expressed further curiosity regarding my sporting interests in the past. Feeling slightly irritated and intimidated by the old man’s persistence I announced that I had been a member of the Irish Olympic rowing team, which competed at Henley in 1948. He was most interested in this information and casually mentioned that he had rowed for Cambridge in the Boat Race. It emerged that he had also played golf for England and that painting and fishing were his main interests apart, of course, plastic surgery. Shortly afterwards I was called in to see the medical superintendents who, after a few perfunctory remarks, told me that Sir Harold Gillies had interviewed me in the hall and that my application was satisfactory. During the ensuing three years at Rooksdown House, Sir Harold made no reference to our unconventional interview.

A second hospital – Queen Victoria Hospital – was assigned to Harold Gillies’ younger cousin, Archibald McIndoe. Dr. McIndoe started working with Harold Gillies prior to World War II in the United Kingdom. Dr. Gillies facilitated his advancement, even relinquishing his role as a consultant physician for the Royal Air Force for him in 1938. Interestingly, Archibald McIndoe maintained his civilian status while working with the military to eliminate rank and other military formalities among the hospital staff to boost and maintain morale. He changed the color scheme of the hospital to brighter colors, believing the appearance of the hospital could affect the emotional health of patients. He even encouraged the local population to visit the hospital and the patients, which was very unusual at the time. His appreciative burn patients – those individuals whose burns were so severe they required surgical treatment – formed the “Guinea Pig Club” and met annually after World War II to toast the plastic surgeon who treated them. Dr. McIndoe would also teach and influence Ivo Pitanguy.

Source: Martin, Paula J. Suzanne Noel: Cosmetic Surgery, Feminism and Beauty in Early Twentieth-Century France. Burlington, Vermont: Ashgate, 2014. Print.

Cosmetic Surgery

It is important to note that most plastic surgeons practiced both reconstructive and cosmetic surgery during this period. In fact, Harold Gillies developed a robust cosmetic surgery practice after World War II, partially because he could not otherwise retire comfortably. Archibald McIndoe also developed a busy cosmetic surgery practice, becoming known for his “McIndoe Nose” which distinguished those patients who underwent rhinoplasty surgery with him.

Cosmetic plastic surgery was widely considered a “lesser” specialty and was ridiculed for focusing on largely healthy patients. The level of scorn directed toward the physicians who practiced cosmetic plastic surgery varied depending on their level of self-promotion as well as their level of engagement with the lay public. Facial plastic surgery in the late 19th and early 20th century was most often employed to “pass” in public, to blend in rather than stand out. This had both positive and negative connotations and may also have contributed to the fact that many of the plastic surgeons performing cosmetic surgery at the time were considered charlatans.

John Orlando Roe, an ENT surgeon from Rochester, became known as the father of cosmetic rhinoplasty, publishing papers on modifying the nasal tip and bridge in the late 19th and early 20th century. He initially became known for treating collapsed nasal bridges, called a saddle nose deformity, in patients who contracted syphilis. There were severe legal restrictions in the United States to advertising as a physician at the time. He was considered one of the more noble cosmetic facial plastic surgeons because he did not advertise and was not ostentatious.

The German plastic surgeon Jacque Joseph was a European contemporary of John Orlando Roe. Like Dr. Roe, Jacque Joseph espoused the psychological benefits of cosmetic plastic surgery. Dr. Joseph was initially allowed to operate only at Jewish hospitals due to the antisemitism prevalent in Germany during this time. In fact, Jacque Joseph maintained dueling scars on his face to better “pass” in German society and avoid this. He even had requests from others to create “dueling scars” on their face to better “pass” themselves. However, even the Jewish hospitals eventually banned him from operating because he was performing cosmetic plastic surgery.

Professional opinions about him changed when World War I broke out and his expertise was required to treat the war-wounded. He was recruited to work as the Director of Facial Plastic Surgery at Charite Hospital in Berlin during the war. He transitioned to private practice after World War I to refocus on cosmetic plastic surgery. His innovations included techniques to reshape nasal bones during rhinoplasty (osteotomies). He also performed facelifts and body plastic surgery. He became internationally renowned, drawing even Americans to visit him. He was reportedly very secretive, having his nurse keep his instruments under towels to prevent visitors from copying his designs. His great contribution to the medical literature was the textbook Rhinoplasty and Other Facial Plastic Surgery published in 1931. This textbook was the first to include photos of post-operative patients smiling after their recovery.

Another great European facial plastic surgeon of the early 20th century was the French physician Suzanne Noel. Born in 1878, she came of age in La Belle Epoque when the women’s rights were improving in France, which likely influenced her drive. She married Henry Pertat, a dermatologist 9 years her senior, at age 18. He was able to start a dermatology practice with family money. French law at the time dictated that women needed permission from their husband to attend medical school. Laws even required husbands to be informed of where their wives were going and the “general spirit” of any conversation they had with others outside of the house. Fortunately for the world, Henry encouraged Suzanne to pursue medicine.

Suzanne passed the externat to function as an extern at Paris Hospital in 1908 at age 30, the same year she gave birth to her daughter Jacqueline. After 2 years as an extern and earning high marks in her testing she started a 4-year internship as a resident physician. She worked in the public hospitals in the morning and at her husband Henry’s dermatology practice in the afternoons.

Her two most influential teachers during her internship were Hippolyte Morestin and Jean-Louis Brocq. Hippolyte Morestin was a French surgeon who became famous during World War I. He was especially concerned with reconstructive surgery and the concealment of scars. He taught Suzanne to be decisive and to take risks in the operating room. The Spanish flu would kill Dr. Morestin in 1919, a tragedy that would befall her daughter in 1922. Jean-Louis Brocq was a dermatologist who first exposed Suzanne to cosmetic plastic surgery. She developed an interest in cosmetic plastic surgery after being visited by the famous actress Sarah Bernhardt, who had undergone a brow lift by the plastic surgeon Charles Conrad Miller in Chicago. She felt she could have done a superior job. Dr. Brocq allowed her to perform cosmetic surgery procedures on volunteer patients during her internship.

Suzanne ran her husband’s dermatology practice when he left for the front lines during World War I. Unfortunately, he suffered from chlorine gas exposure while testing gas masks, which permanently disabled him. He was forced home from the front lines in 1918 where he died from respiratory failure.

Suzanne married Andre Noel, her medical school classmate and close friend, in 1919. Like her first husband, Andre pursued dermatology. In fact, Andre took over Henry’s dermatology practice after he died. This is partially because, at the time, a woman could only practice medicine under a male physician’s license. Suzanne could run the dermatology practice but was not allowed. Suzanne gave her medical school thesis – a device that used air pressure to spray jets of medication impregnated water on the skin of patients – to Andre so he could run the dermatology clinic. The couple would later commercialize and sell the device.

Andre became depressed after Jacqueline’s death and committed suicide in 1924. Left with a dermatology practice she could not run because she never submitted a thesis (women could practice independently with a license now), Dr. Noel quickly wrote a thesis on the topic of the big toe, partially to slight the leadership at the University of Paris for previously restricting her practice of medicine. She would acquire her medical license in 1925, allowing her to run the dermatology clinic.

Her cosmetic surgery practice quickly became popular, which allowed her to pay off the enormous debts Andre had accumulated during his depression. She operated out of her apartment in Paris near the Hotel George V, because cosmetic plastic surgeons were generally not allowed to operate in hospitals in France at the time. She eventually outgrew her apartment, moving her private practice to the prestigious Clinique des Bleuets. She also promoted the practice of cosmetic plastic surgery around Europe, advocating the psychological benefits of plastic surgery like Dr. Roe and Dr. Joseph. She travelled to Germany to advocate for the founding of a Department of Social Cosmetics at the Institute for Dermatology at the University of Berlin. Berlin was one of the few places in the world where cosmetic surgery was considered acceptable as a form of “mental hygiene.” This was during the time that Jacque Joseph was becoming famous for his rhinoplasty techniques while practicing in Berlin.

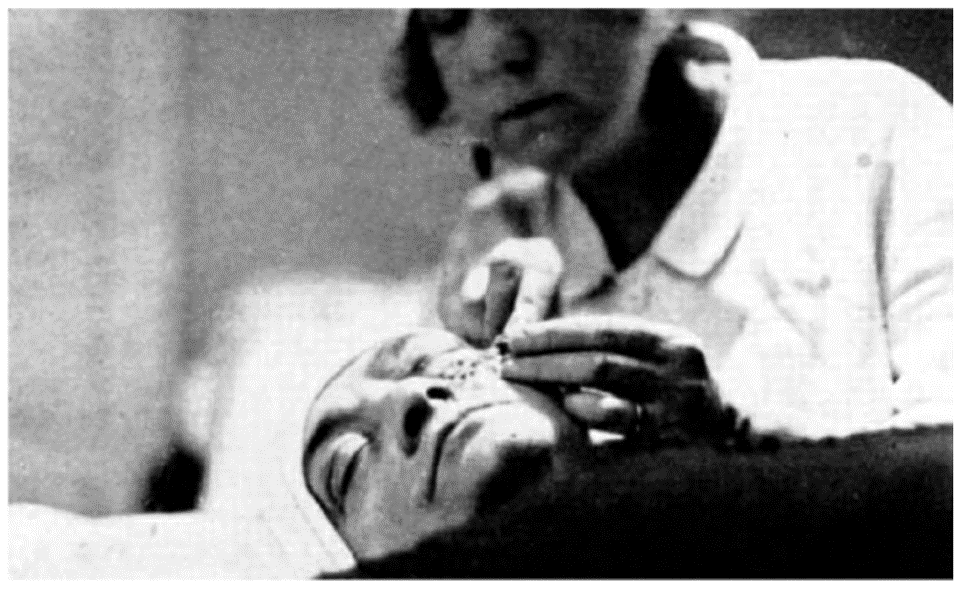

Dr. Noel published Aesthetic Surgery and its Social Significance in 1926. This textbook was immensely popular, being translated into other language and further establishing her reputation. Her contributions to the field of plastic surgery were numerous. They included the pioneering use of long, elliptical incisions along the hairlines during face lifting operations. She invented the craniometer, a device which allowed her to measure facial dimensions more precisely. She improved on a now-common approach to lower eyelid surgery and the facelift. Probably most importantly, she successfully combined local anesthetics with epinephrine to reduce bleeding and improve patient comfort during surgery, a generally accepted practice today.

She also took a more patient-centered approach to practice and teaching. She was one of the first surgeons to include actual photos of the steps of her operations in her textbook. She discussed surgical options and expected results with her patients. She allowed her patients to decide between local and general anesthesia. She was obsessed with concealing the effects of surgery, going so far as to formulate tinctures matching various hair colors to dye the bandages she placed on patient’s hairlines. She also provided tea and lunch to her patients after surgery.

It was for her accomplishments that she was awarded The Order of the Legion of Honor in 1931, a rarity for women in France.

In contrast with Drs. Roe, Joseph, and Noel, Joseph Sheehan was considerably showier and more ostentatious. He was born in Dublin, Ireland in 1885 and emigrated to the United States. Relegated to poverty after the death of his father, he managed to gain admittance to Yale Medical School and trained with Harold Gillies at Sidcup during World War I. He returned to the United States and practiced in New York City. He became enmeshed in bad press after inviting a New York Times reporter back to his office after a lecture he was asked to give to the New York City Police Department. The reporter described the extravagance of his office rather than the lecture he was being interviewed about. He also attracted considerable controversy because he was a supporter of the Spanish dictator Francisco Franco, helping to organize hospitals and train surgeons in Franco’s army.

Joseph Sheehan was deeply connected to the concept of the use plastic surgery to “pass” in society. Convicted criminals sought out facial plastic surgery in the early 20th century to escape detection by authorities. Dr. Sheehan was giving a lecture to the New York City Police Department about what could and could not be accomplished with plastic surgery at the time so that the police force could better detect individuals attempting to evade them. This panic is what led to European and American criminal authorities to tattoo convicted criminals.

One of the most famous examples of a criminal undergoing facial plastic surgery to evade the police was John Dillinger, the leader of the Dillinger Gang which robbed banks and police stations during the Great Depression. John Dillinger was arrested and killed in 1935 along with the plastic surgeon who performed a rhinoplasty and facelift on him to conceal his identity. Even J. Edgar Hoover became involved, warning plastic surgeons of the risks in aiding criminals. A more modern example is the drug trafficker Richie Ramos who underwent rhinoplasty, liposuction, and excision of gunshot scars from his face to evade the police. He and his plastic surgeon, Dr. Jose Castillo, were arrested in 1997 for obstruction of justice.

There was not only a concern in the early 20th century that criminals would undergo facial plastic surgery to conceal their identity. Some also theorized that one could change criminality by changing the appearance of criminals. In fact, some prisons offered to pay plastic surgeons to operate on jailed criminals. One example was a pilot project at San Quentin in 1927 examining the rehabilitative effects of facial plastic surgery which was initiated by the convicts themselves. As expected, this project would prove unsuccessful.

Source: Simons, Robert L. Coming of Age: A Twenty-Fifth Anniversary History of the American Academy of Facial Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. New York, New York: Thieme Medical Publishers, Inc., 1989. Print.

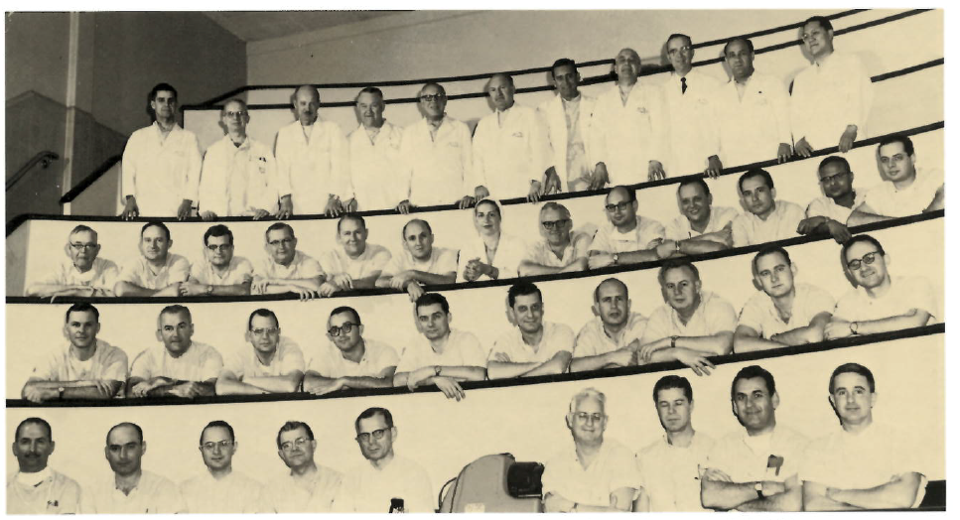

Professionalization

The professionalization of the field of facial plastic surgery followed World War II. The founders of the field remained marginalized from professional circles. As a result, they were forced to develop some the earliest standardized training programs of any subspeciality. And even within the field of facial plastic surgery there was conflict between those who felt the emphasis should be on reconstructive versus cosmetic surgery. That distinction is best exemplified by two individuals, Maurice Cottle and Irving Goldman. Both individuals were taught by Samuel Fomon.

Samuel Fomon was not a surgeon but an anatomy teacher who nevertheless was operating. He compiled all known work on facial plastic surgery and taught it at a time when general plastic surgeons were excluding ENT/facial plastic surgeons from this knowledge. He gained this knowledge while traveling abroad, specifically to Germany where he visited Jacque Joseph. He confirmed Jacque Joseph’s penchant for secrecy. He even paid Dr. Joseph’s nurse to see his instruments, sketched the designs and returned to the United States to re-create these instruments for use during his course.

He initially established the Fomon Course in the 1940s in Manhattan General Hospital, one of the few places where formal instruction in facial plastic surgery was available. Students would pay an “assistant’s fee” to operate on the patients. Samuel Fomon’s wife, who was a physician, assembled his textbook and functioned as the in-house artist who double-checked his work.

He was initially ostracized from universities in the United States until Dr. George Coates of Philadelphia, a well-respected ENT and editor of Archives of Otolaryngology, started to encourage the University of Pennsylvania residents to attend his course. This endorsement, as well as the endorsement of the course by the chairman of the Department of Otolaryngology at the University of Iowa, Dr. Dean Leirle, legitimized the course in the eyes of other universities. Maurice Cottle and Irving Goldman both attended the Fomon Course.

Maurice Cottle emphasized the importance of functional rhinoplasty over cosmetic rhinoplasty. He later created his own course on rhinoplasty. He was obsessive, reportedly dedicating an entire decade of courses to individual components of the nasal anatomy, starting with the septum and ending with the bony pyramid in the fourth decade of his course. He was reportedly a difficult teacher, but fair. In fact, he was as difficult on the chairmen of otolaryngology departments as he was on new trainees. He also always made sure that the nurses, janitors, electrician, carpenters, and anyone else who assisted in putting on the course received a gift of appreciation. He became known for his sayings, or “Cottle-isms” including “never do in nasal surgery something that you cannot undo” and “the best operation is one we don’t have to do…we are second best.”

In contrast, Irving Goldman emphasized the cosmetic approach to rhinoplasty. Born in 1898 in New York City, he was initially trained as an ENT but then developed an interest in cosmetic rhinoplasty. Like other facial plastic surgeons at the time, he was excluded from the establishment by general plastic surgeons. It took time but he eventually established himself at Mt. Sinai Hospital in New York City. He was initially not allowed to perform cosmetic rhinoplasty surgery at the hospital; that is, until he performed the procedure on two of the daughters of the chief of medicine there. He eventually performed many of the revision rhinoplasty procedures of the general plastic surgeons who initially excluded him. He started a course emphasizing the aesthetic aspects of rhinoplasty in 1950. The Goldman course became the longest running course in rhinoplasty. Dr. Goldman would eventually become the first president of the American Academy of Facial Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery (AAFPRS).

Source: Holzer, John. Plastic Surgery Obsession: Brazil’s Dr Ivo Pitanguy Triggered it All. Houston, TX: Alto Press, 2011. Print.

Ivo Pitanguy

The Brazilian surgeon Ivo Pitanguy was a product of the development and professionalization of the field of plastic surgery. He was a pioneer in reconstructive and cosmetic facial plastic surgery, importantly outside of the traditional centers of Europe and the United States.

Dr. Pitanguy’s origins were modest, but his training was top notch. He started as a general surgery resident largely working out of an ambulance in the favelas of Rio de Janeiro. He won a scholarship to study reconstructive plastic surgery under John Longacre in Cincinnati at Bethesda Hospital in 1948. He then travelled to the United Kingdom to study under Harold Gillies and Archibald McIndoe under a British Council Scholarship. Dr. Gillies encouraged him to teach and perform research while McIndoe encourage him to perform cosmetic plastic surgery. The reporter Joan Kron reported in her book Lift: Wanting, Fearing, and Having a Face-Lift, that "once, while [Pitanguy was] watching Gillies do a facelift...Gillies said something inspirational: 'If I didn't think this had value, I wouldn't do it."

He returned to Rio de Janeiro in 1952 where he started a burn unit to treat the direst patients. It was at this hospital that he mobilized his team to treat hundreds of patients who were severely burned during the Niteroi Circus Fire, the worst indoor fire disaster ever. He was a workaholic, practicing on cadavers at night. Interestingly, he was reportedly never mugged when walking the streets of Rio de Janeiro at night because the formaldehyde left him with the “smell of death.” It was at this institution that he developed a training program for plastic surgery based on the American residency system for training new physicians. Dr. Pitanguy not only taught residents but also proselytized plastic surgery to other specialties. This differed greatly from other plastic surgeons like Jacque Joseph who hid their techniques.

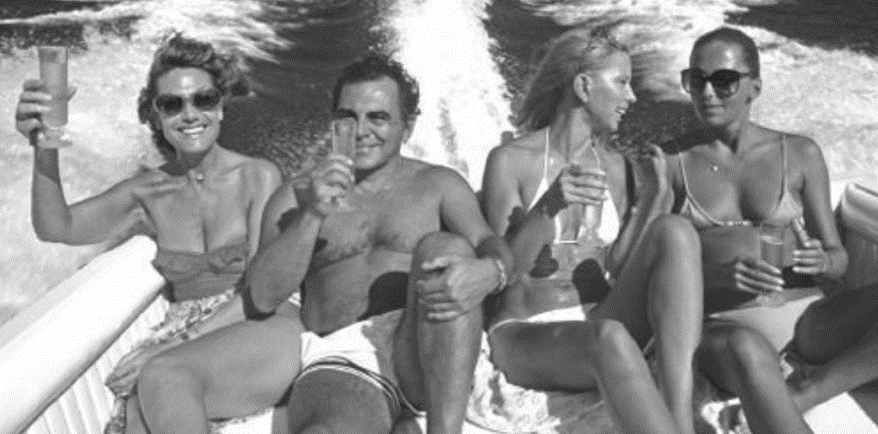

He followed up the founding of his clinic with the founding of the world’s first plastic surgery hospital called Clinica Ivo Pitanguy in Rio de Janeiro in 1963. This hospital provided a luxurious experience for patients. It was through this hospital that Rio de Janeiro became a center for plastic surgery. The city was popular with jet setting royalty and movie stars at the time. Ivo Pitanguy’s reputation spread from there.

He was also a scholar. His contributions to the medical literature were immense. He published Aesthetic Surgery of the Head and Body in 1981, which is considered a classic textbook. He identified the Pitanguy Ligament in the nose, which is an important structure when performing rhinoplasty. He also identified Pitanguy’s line, which follows a branch of the facial nerve up the forehead and is an important marker for head and neck surgery.

One of the most fascinating things about Ivo Pitanguy was his personality. His skills and work ethic were legendary. He was ambidextrous and could operate equally well with his right and left hands. He would routinely operate 12 hours daily then go immediately to a black-tie event in the evening. He assembled an excellent team to facilitate this productivity. He was also very sociable and warm, another unusual trait for surgeons at the time. He spoke 6 languages fluently. His patients included movie stars such as Brigitte Bardot, Frank Sinatra, and Michael Jackson, whose scalp he repaired after it was burned while filming a Pepsi commercial. He treated royalty including empress Farah Diba of Iran. He also treated political royalty including Jackie Onassis and Rosalynn Carter.

He was also unusually open with the press. This was partially facilitated by the fact that there were fewer legal and cultural restrictions against self-promotion in Brazil compared with the United States and Europe. An article in Time magazine in 1967 helped spread his fame internationally among non-surgeons. One of his patients wrote a book titled The Beautiful People’s Beauty Book in 1971, which was the first public glimpse inside the world of plastic surgery. He earned the respect and, unfortunately, jealousy of many plastic surgeons because of his skills and fame. For example, many European countries recruited him to operate but subsequently withdrew his privileges because of his popularity. Joan Kron explained that "it would take years for the medical establishment to accept the fact that publicity and charlatanism didn't necessarily go hand in hand."

In the end, Ivo Pitanguy had the last laugh. The institutions he built, the physicians he trained, and his contributions to the medical literature are inalienable. His life inspired Vinciciu de Moraes, the writer of the song “The Girl from Ipanema” to coin the new Portuguese verb Pitanguizar, which means to create beauty. According to Joan Kron, who had an opportunity to spend time with Dr. Pitanguy before he passed, he explained that his goal was "to give age a dignified expression, a frame the spirit can inhabit" while being "adamant that surgeons - or anyone else, for that matter - should not impose their vision on the patient."

Conclusion

Harold Gillies, Archibald McIndoe, John Orlando Roe, Jacque Joseph, Suzanne Noel, Joseph Sheehan, Maurice Cottle, Irving Goldman, and Ivo Pitanguy stood on the shoulders of giants. Now giants themselves, newer generations of facial plastic surgeons are advancing on their discoveries and innovations. Among the major lessons about the lives of these individuals is that the reconstructive and cosmetic side of facial plastic surgery are both important and essential. Each area of focus informs the other. A second major lesson is the importance of being inclusive. Suzanne Noel, Jacque Joseph, and Ivo Pitanguy were all discriminated against in some way, but they persevered and contributed immeasurably to the field of facial plastic surgery. Future advances will depend on identifying and supporting talented surgeons regardless of their background.

Trust Your Face to a Facial Plastic Surgeon

It is important to seek a double board-certified, fellowship-trained specialist in plastic surgery of the face and neck when you have concerns about your face or neck.

Why Choose Dr. Harmon

- The mission of Harmon Facial Plastic Surgery is to help people along their journey towards self-confidence, to feel good about feeling good.

- Dr. Harmon is a double board-certified facial plastic surgeon.

- Dr. Harmon values making patients feel welcomed, listened to, and respected.

- Dr. Harmon graduated with honors from Cornell University with a Bachelor of Science degree in molecular biology.

- Dr. Harmon earned his medical degree from the University of Cincinnati.

- Dr. Harmon underwent five years of extensive training in head at neck surgery at the prestigious residency program at the University of Cincinnati.

- Dr. Harmon then underwent focused fellowship training in cosmetic facial plastic surgery through the American Academy of Facial Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery (AAFPRS) with the world-renowned surgeon, Dr. Andrew Jacono, on Park Avenue in New York City.

Request a Consultation

Request a consultation with Dr. Harmon at Harmon Facial Plastic Surgery in Cincinnati. Visit our clinic. You will learn more about Dr. Harmon’s credentials, style and approach. Build a relationship with our dedicated team. Do not stop at searching “plastic surgery near me.” Get in touch with us today to learn more!

References

- Gilman, Sander L. Making the Body Beautiful: A Cultural History of Aesthetic Surgery. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1999. Print.

- Haiken, Elizabeth. Venus Envy: A History of Cosmetic Surgery. Baltimore, Maryland: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1997. Print.

- Holzer, John. Plastic Surgery Obsession: Brazil’s Dr Ivo Pitanguy Triggered it All. Houston, TX: Alto Press, 2011. Print.

- Martin, Paula J. Suzanne Noel: Cosmetic Surgery, Feminism and Beauty in Early Twentieth-Century France. Burlington, Vermont: Ashgate, 2014. Print.

- Meikle, Murrary C. Reconstructing Faces: The Art and Wartime Surgery of Gillies, Pickerill, McIndoe & Mowlem. Otago University Press, 2013. Print.

- Mendelson, Bryan. In Your Face: The hidden history of plastic surgery and why looks matter. Richmond, Virginia: Hardie Grant Books, 2013. Print.

- Simons, Robert L. Coming of Age: A Twenty-Fifth Anniversary History of the American Academy of Facial Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. New York, New York: Thieme Medical Publishers, Inc., 1989. Print.

Disclaimer

This blog post is for educational purposes only and does not constitute direct medical advice. It is essential that you have a consultation with a qualified medical provider prior to considering any treatment. This will allow you the opportunity to discuss any potential benefits, risks, and alternatives to the treatment.

Book Your Consultation

Take the first step toward enhancing your natural beauty by scheduling a personalized consultation with Dr. Jeffrey Harmon. As a double board-certified facial plastic surgeon trained by the pioneer of the extended deep plane facelift, Dr. Harmon offers expert guidance and care. Whether you're considering surgical or non-surgical options, our team is here to support your journey to renewed confidence.